The grandest of all human sculptures are, in fact, the work of the planet's poorest people. Unable to find a job or a plot of land in the valley, the most disadvantaged people of the developing world carve mountains to grow their food. Mountainside farming offers an extraordinary spectacle. A single slope can be covered with hundreds of terraces, themselves carved up into dozens of little parcels separated by walls made of earth or stone. Whether they take the form of flooded rice paddies mirroring the sky or successive green steps of wheat, these thousands of tiny plots climbing up the mountain fill the eye with admiration.

The problem with terraced mountainsides is that they hide a cruel irony. While many would agree that mountain farming is a visual success, there is much less accord about its viability. In fact, the record of mountain farming is one of repeated disaster. The soil of the marshlands that surround modern Italy once covered the mountains that are now denuded and eroded. Archeologists also attribute the catastrophic erosion of the mountains and hills of ancient Greece to successive waves of deforestation. Yet these same experts can point to remarkable examples of durability. In Greece, for example, the terraces that were built in Plato's time have withstood the ravages of erosion for more than two thousand years.

What will the archeologists of some future millennium have to say about the farmers who today cultivate the slopes of the Andes, the Himalayas and the mountains of Central Africa?

Today, two-thirds of the non-irrigated farmland in developing countries suffers from some degree of limitation on its productivity: acidity, aridity, salinity or erosion. Ten percent of this land, located on the flanks of mountains, is especially vulnerable to erosion.

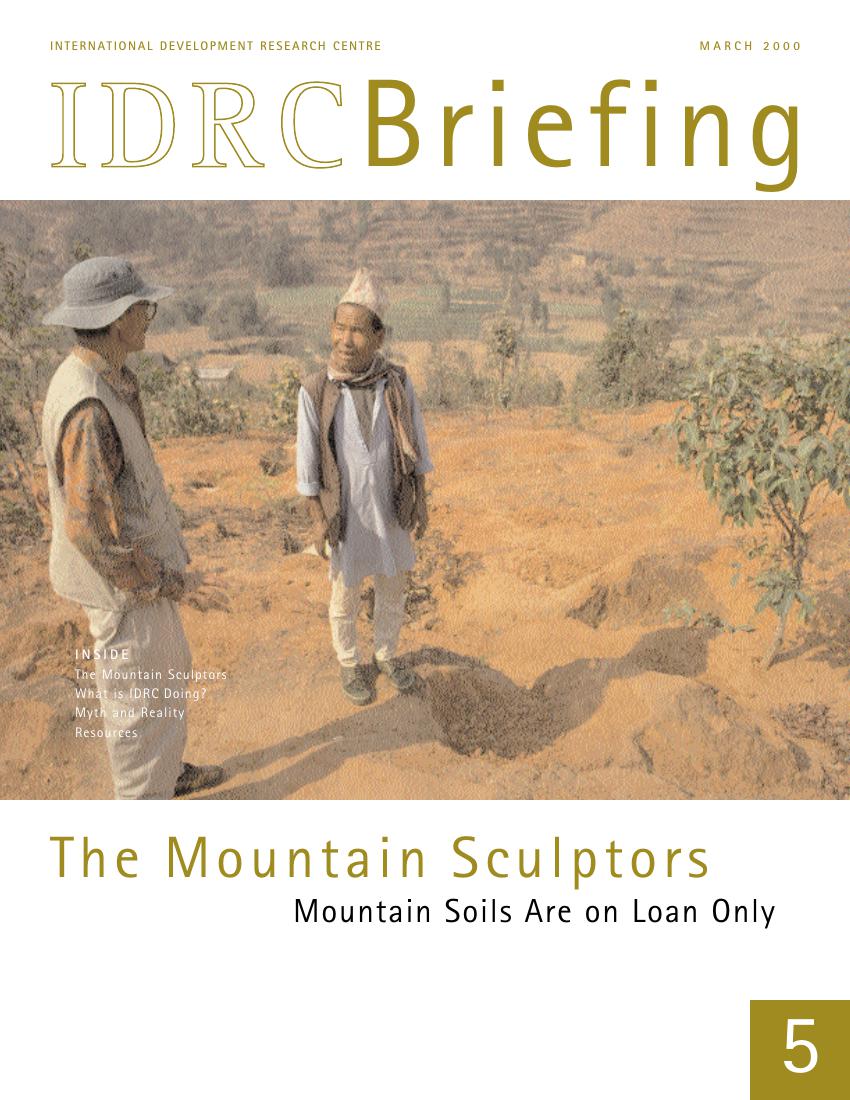

In many of these lands, where on the average people can rely on plots of land measuring only 30 metres by 50 metres, the mountains are under a state of siege. Nepal is a good example of a country where the limited supply of farmland is under constant and increasing demographic pressure. With the highest mountains in the world, and one of the fastest-growing populations (2.6 percent), the Kingdom of Nepal represents a veritable laboratory for studying the impact of farming on mountains. Few Alpine environments have been so thoroughly shaped by man as the middle ranges of Nepal, located between the peaks of the high Himalayas to the north and the Indian plain to the south.

Since 1989, a team from the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), mainly funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation and with support from IDRC, has been studying farming in the valley of the Jhikhu River, located some 40 kilometers to the east of Kathmandu. After 10 years of research, scientists examining this valley of 11,000 hectares, located at altitudes of between 750 and 2,100 meters above sea level and inhabited by more than 33,000 people, have painted a picture of a land that is on the brink of exhaustion.

International Development Research Centre (IRDC) www.irdc.ca